A Classic Kitchen Accessory Mounted with a French Cleat

By Rob Robillard

In this article I cut a 100-year-old, recycled slate chalkboard and create a custom-sized frame to hang it in. A client of mine came across an old slate blackboard that was salvaged from a boarding school. This blackboard was originally installed in the French classroom of the school more than a century ago and was recently replaced with a whiteboard during a remodel.

Our client loved the antique look and feel of the slate and wanted to make a smaller chalkboard for their kitchen. They had a small space in mind, approximately 20 x 54 inches, in front of an exposed brick chimney.

Salvaged slate chalkboard has a beautiful, aged look to it. It’s a creative alternative to traditional chalkboards, and the look complements many designs and home projects.

Design the Frame

The first step in many projects like this is to determine the size of the chalkboard. Remember that width and measurement will be the frame edges, and the slate will be cut smaller to fit into this frame, similar to a picture frame.

We decided that a 2-1/2-in. wide frame was not only a nice proportion but looked similar to the surrounding trim and cabinet styles. We also wanted to include a 3/8-in. radius bead along the inside edge of the frame for aesthetics and to complement the existing bead-board backsplash in the kitchen.

Real slate chalkboard is heavy, and we figured that we would need to mount this on the brick chimney with masonry screws and a French cleat.

A French cleat is a sturdy way to secure a heavy item to a wall. It involves using two ‘cleat’ boards, each with an opposing 30-45 degree bevel. One cleat is mounted to the wall and the other to the item you want to hang. The bevels interlock and secure the item to the wall. Because no fine maneuvering is required, even a relatively heavy cabinet can be hung this way.

Cut the Frame

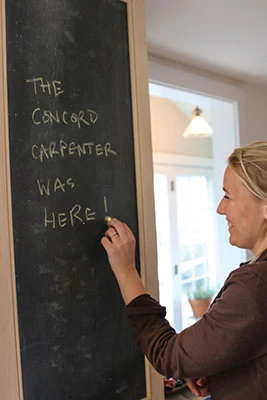

This was a paint-grade project so we used clear, select pine for the frame, because it has little to no knots. We could have also used Poplar species, which is a cheaper alternative and is also known for its “knot-free” qualities. I took our materials into my “Concord Carpenter” shop and began construction.

The first step was to cut the chalkboard frame sides (long parts) to the exact height of our project. Next, I cut the top and bottom pieces to the exact width. Because we were mitering the frame corners, all four parts could be cut to the final length and width.

After choosing the “best face” of the wood, I routed a bead along one entire edge of all four-frame parts. I used a 3/8-in. radius router (with ball bearing bit) mounted in a router table. The ball-bearing guide on the router bit ensures that you get a consistent bead along the entire length. I used a router table fence only because I wanted to use my dust-collection system. I’m a huge fan of collecting dust at the source during long-term sanding applications.

Once the routing is complete I used a block plane to remove the mill marks that the router bit leaves behind. I then used 100-grit sandpaper to sand the bead and lightly break (round off) the sharp routed edges.

Make the Rabbet

The next step is to cut a rabbet to recess the slate into. A rabbet is a recess or “one-sided” groove cut into the edge of the frame. The purpose is to hold the slate and allow a back cover to attach flush to the frame. This allows you to “lock” the slate securely into the frame.

I measured the slate in numerous locations and found it to vary in thickness. The average thickness was 1/4 inch but there were some thicker spots so I made the rabbet 5/16 inch deep and wide.

I figured a secure fit was better than a loose fit, and knew the 1/4-in. plywood backing board would span over any areas larger, further holding the slate in place.

Using a 1/2-in. rabbet router bit and a router fence, I set the width and depth the cut a rabbet on the opposite face of the newly routed 3/8-in. bead.

Assemble the Frame

I cut 45-degree miters on the frame parts and dry-fitted them and the slate to see how things were fitting. Once satisfied with the fit I used a Festool DF500 Domino cutter to cut slots in the miter joints.

Dominos provide a mortise-and-tenon joint, which is super strong, and durable. A biscuit joiner and biscuits can also be used for this purpose but are not nearly as strong a joint.

I then glued the dominos and miters together and clamped it overnight. The next morning I removed the clamps, then cleaned up the face frame with a random orbital sander and some hand sanding. I then cut the 45-degree beveled French cleat out of some scrap plywood. Plywood does not split like regular wood when installing fasteners.

I cut additional strips of pine to line the sides and bottom of the frame in order to hide the French Cleat hanging system. Doing this adds an additional 3/4-inch to the depth or projection of the chalkboard on the wall but it’s needed. Personally, I like the added depth and think it gives a nice, sturdy look to the frame.

Cut Slate to Size

We then measured our slate opening and reduced the measurement by 1/8 inch off the width and length.

I set up sawhorses outside and used 2×4 slats to support the slate. I also made sure to support the area beneath the cut line. I measured and marked the slate with a permanent marker and a straight edge.

Compared to other stones, slate is fairly soft. You can cut it using a grinder, wet saw, or a circular saw—all equipped with a diamond blade. On this job I used a Bosch grinder with a diamond-cutting blade and paired it with a Festool HEPA vacuum to collect the dust while cutting. I also used a dust-collection hood for the grinder that had a nice flat cutting plate to guide the grinder along the slate.

I set the grinder to cut through the slate and into the 2×4 wood 1/8 inch deep to account for irregularities in the slate thickness. I then slowly cut “free hand” through the slate (easy cutting).

If desired, a straight edge can be clamped to the slate to assist the cut application.

Add Slate and Backer

After cutting the slate I checked the fit in our frame, then cut a 1/4-in. plywood backer-board 2 inches larger in both the width and length of the slate. The extra material overlapped the slate by an inch on all sides. The backer-board is fastened with 1/2-in. crown staples through the over-lapping edges.

Once the backer-board was applied, I added the pine side strips to the rear of the chalkboard frame using glue and brad nails. I also glued and screwed our 45-degree bevel French cleat to the top section of the frame back.

Make the Chalk Shelf

Once the frame, slate and backer-board were assembled, I had a good idea of how this project was going to look and decided to add a chalk shelf. This would add 3/4 inch to the overall length of the project, but we had the extra room.

I took a 3-in. piece of pine the same width as the chalkboard frame and added a chalk-holder slot to it with a thumbnail router bit. I wanted the shelf slot to start approximately 1 inch in from the sides, to prevent the chalk from sliding onto the floor.

The key is to carefully mark out the slot on the board as a visual reference during the design phase, and more importantly, mark the backside of the board for the routing application. When routing on a router table, the groove will be face down, and you will not be able to see it.

I placed center-mark reference on the router fence, where the router bit was located. This allowed me to drop the shelf down onto the router bit, one inch inward from the edge, and then stop it one inch from the opposite edge. The resulting groove looks similar to a fluted column.

In the final step of construction, I filled nail holes or imperfections with wood filler, sanded, wiped off the dust and applied primer and two topcoats of quality paint.

This step can actually be done before the slate is installed, but I chose not to do so.

Hang the Chalkboard

After installing the plywood cleat to the chalkboard frame, the opposing cleat is installed to the brick masonry with Tapcon masonry screws. Leave the masonry cleat slightly smaller in width so you can fine-tune the left/right placement for perfect positioning.

I measured and marked the location of the cleat, leveled it and then used a rotary hammer to drill pilot holes into the masonry.

Tip: Drill and install one masonry screw first, then recheck the level and drill the second and any subsequent screws.

On a regular wall you would install this cleat to span across wall studs, then use screws to fasten to the studs. Other-wise you will need wall anchors or toggle bolt to mount it between studs.

Slate Finish Tips

I used a beater chisel and later a razor blade to remove old caulking and paint buildup around the slate edges. Although these edges were going to be hidden by the frame rabbet, I wanted to remove it for a better fit.

For deep scratches and the removal of surface grime, use a random orbital sander with fine grit sandpaper. Wet the abrasive and use a little water to keep dust down.

In the end, the slate proved to be a strong choice for a number of reasons. It’s easy to cut, making it simpler to work with than many might expect. The slate will last for decades unlike MDF or other imitations, it serves as a useful kitchen accessory, and in this case it tied the house to the history of the region.