A friend of ours here at the EHT headquarters decided he wanted a new hardwood floor, but wasn’t excited about the hassle of installation or the high-price of contracting the labor. The solution was laminate hardwoods. Laminate flooring offers the classic look of solid hardwoods, but it fastens together seamlessly, without the mess of glue. The floorboards simply snap together using a tongue-and-groove system. The interlocking planks create a strong, tight joint that secures the flooring from wall to wall. The result is a beautiful new upgrade to the room. And the quick installation makes adding a new laminate floor ideal for the weekend warrior.

Laminate flooring is manufactured from high-density fiberboard planks covered with decorative laminate sheeting and a clear plastic wear layer. Choose from a wide variety of wood appearances, such as oak, cherry, walnut, beech and many other options. And many new laminate flooring lines show remarkable attention to detail with the textures of the top surface. You’ll find a wide range of ultra-realistic textures that look and feel like real wood, including worn, rustic looks and high-gloss finishes.

Durability is another key feature. Many laminate flooring products are impervious to most stains and very resistant to scratches. The boards are prefinished at the factory and often feature a built-in edge sealant that protects against moisture absorption. Some laminate flooring manufacturers even offer a lifetime wall-to-wall warranty against wear-through, stains, fading and water damage from everyday spills and damp mopping.

It turned out that laminate flooring was just what this homeowner was looking for, and he chose the Pergo Select brand of flooring in a “Smoked Oak” style. Here’s how we installed it.

To cut the door jambs to allow clearance for the floor, we used a Rotozip equipped with a flush-cutting attachment.

Stick with a Plan

Your first step is to lay out a floor plan. Sketch the room on paper and mark the dimensions. Calculate the square footage you’ll need, and then order extra to account for unusable cut planks, as well as providing some extra material if damaged planks need to be replaced in the future. Also make note of the different transitions in the room where the laminate will meet other types of flooring or exterior doors. The home store where you purchase the flooring will usually have transition moldings for these areas.

Once the flooring is on site, allow the unopened cartons of planks to remain in the room where they are to be installed at least 48 hours prior to installation. This allows the flooring to shrink or swell slightly, according to the climate of its new home.

After prepping the floor, we installed the foam underlayment. If installing over concrete, a moisture barrier would be required between the subfloor and underlayment.

Laminate can be installed over most flooring surfaces, but always remove carpeting and remove any wood flooring that is installed over concrete. In this case, we dealt with carpet removal, which meant pulling up about 10 billion staples that held down the pad—no fun at all.

Next, make sure the subfloor is clean, dry and level. We got off easy, because this floor was going in the second-story entertainment room, which had a nice, flat plywood subfloor. The laminate planks must fit together correctly to ensure an even finished surface and a seamless appearance, so a flat subfloor is critical. Check for level with an 8-foot straightedge laid across the subfloor. Most manufacturers recommend no more than a 3/16-inch difference in height between any two points in a circle with a 20-foot diameter. If the floor isn’t this level, you’ll need to fill low spots or grind down high spots before installing the flooring. Building paper can be used to fill low spots less than 1/4-inch deep, but you’ll need a Portland cement-based leveling compound to fill deeper depressions.

Cut the registers out of the underlayment so nobody accidentally steps into the concealed hole.

Damp floors present another problem for installation. In the project shown, we installed above a finished basement, so we had no moisture problems to worry about. This might not be the case with a concrete slab, so make sure the subsurface is dry. Check the moisture content of concrete floors by taping the edges of a 2-foot polyethylene square over the concrete. After 24 hours, if no signs of moisture buildup or discoloration appear beneath the plastic, the floor is probably dry enough. Otherwise, seal it.

Also, remove any existing base trim along the walls. Because the flooring will expand and contract due to changes in humidity, the planks aren’t installed tightly against the walls of any room. You’ll need to leave a 1/4-inch gap against the wall around the edges of the flooring to allow for the expansion. The spacing must be maintained at every wall in the room. Once the flooring is completely installed, base moulding and/or quarter-round can be reinstalled over the edges to conceal the gap. We used Pergo’s Installation Spacers lined against the wall to ensure consistent spacing. You can also use wood strips.

We placed a “dry run” of loose planks to make sure we didn’t have final planks that were too small at the opposite wall.

Next step: Undercut the doorjambs and casing to allow room for the thickness of the new flooring. A pull saw works for this job, enabling you to get close to the floor to make the cuts. You can also rent an electric jamb saw. For this project we used a RotoZip equipped with its new flush-cutting attachment, which worked like a charm. Determine the required depth of undercut by stacking a scrap of flooring on top of a piece of foam-cushion underlayment and using it as a saw guide, representing a small, workable sample of the final installed floor. Leave an additional 1/4-inch of space concealed beneath the doorframe to allow expansion.

Laying the Laminate

On concrete subfloors, use 6-millimeter polyethylene film as a moisture barrier. Create an 8-inch overlap to join sheets of film when covering the subfloor. The film is needed over all subfloors that contain concrete, even if the concrete is covered with vinyl, linoleum tile or other type of flooring. Again, we were on second-story plywood, so we skipped the moisture barrier and went straight to the underlayment.

When it’s time to install the floor, cut the tongues off the first row of planks.

All laminate floors require a foam underlayment to provide extra comfort and noise reduction. Some brands of flooring even have underlayment attached to the underside of each plank. For this job, it came in a roll. Cover the subfloor with underlayment to the edge of the wall, butting the edges and securing the seams with duct tape.

Before beginning the planks, measure the width of the room to make sure the last row of flooring will be at least 2 inches wide. Divide the width of the room by the width of the exposed face of the flooring. The remaining number will be the width of the last row. If the last row is less than 2 inches, cut the first row of boards narrower to allow more room for the last.

To stagger the joints from row to row, we began the second row with a plank cut to 12 inches long.

We also laid out a “dry run” of planks to make sure we didn’t have a tiny sliver of flooring at either end of the room. According to Pergo’s instructions, the flooring planks should have joints staggered by 12 inches, so calculate the first three rows to make sure the staggered joints won’t result in a plank shorter than 6 inches at either wall. If necessary, adjust your layout so this is not the case.

We then assembled the first row of planks with the tongue side toward the starting wall. However, the tongues weren’t actually there anymore—we cut the tongues off the first row with a circular saw. But these planks have two tongues, one on the side and one on the end. To install the first row, begin with full length planks. Insert the end tongue into the groove of the first plank’s end joint and rotate the plank downward. Continue this with each plank until Row 1 is complete. You’ll probably have to cut the last plank to length.

Maintain a consistent expansion gap around the flooring by using spacers between the walls and the planks.

I should point out that you should follow the directions of your particular product, because laminate flooring doesn’t always install exactly the same. But for this project, we then cut the first plank of Row 2 to 12 inches. Start Row 3 with a cut length of 24 inches. On Row 4, start with a full-length plank again. Repeat this process throughout the room to keep the joints consistently staggered.

To join the planks of Row 2 to Row 3, insert the long tongue of Row 2’s first plank into the groove of Row 1 until the laminate edges meet, and then press downward until the joint locks. There should be no gaps at the joints.

To install the planks, insert the long tongue into the groove of the preceding row. Tilt downward to lock the joint together. Then slide the plank, pushing its short tongue into the preceding short groove.

After completing Row 1, installation gets a little trickier because you have to join both tongues—on the side and at the ends. To do so, first insert the long tongue of Row 2’s second plank into the Row 1 groove and rotate downward. Then, kneel on the first plank of Row 2 while you push together the end joint of the second plank into the first.

Once Row 2 is complete, install Row 3 in the same manner, but cut the first board to keep the joints staggered. Repeat the installation from row to row throughout the room, always keeping the joints staggered. Unless you’re really lucky, you’ll probably have to rip the last row of planks to width, and using a table saw is your best bet for that operation. You can also use a jigsaw to notch planks to fit around various corners or other obstructions in the floor.

You can encourage stubborn T&G joints to lock by using a hammer and a wooden block.

Occasionally you’ll end up with a stubborn plank that doesn’t want to “click” together easily at the tongue-and-groove joint. You can join these with a wood block and a hammer. Align the tongues into the grooves of the short and long sides. Place the block no closer than 8 inches from either end of the plank and tap along the side until the joint is closed tightly.

Another tough spot is installing the last plank on each wall. These planks present a problem because the wall obstructs where you need to be in order to push the end joint together. This means you need a pull bar to pull the last plank into the joint. We used a tool called the Lam-Hammer, a specialty tool designed explicitly for this purpose. It hooks the end of the plank and allows you to jerk it into the joint with its sliding handle. The Lam-Hammer made quick work of these tricky planks.

For tricky end planks, we pulled them into place with a special tool called a Lam-hammer.

After the floor was complete, the result was really striking—a beautiful new floor that took only a weekend to install—and we did it ourselves. You can, too.

Installing Laminate Tile Flooring

Retired art teacher Marsha Graham loves the southwestern look of the ceramic tile floors in her Arizona home and wanted something similar in her Oregon residence. However, she wasn’t convinced that Oregon’s wet and cold climate and tile floors would get along that well. That’s how she settled on a laminate floor with a tile pattern.

In addition to being softer and warmer, the laminate floor would cost less, install faster, and maintain easier than the tile floor in her desert home. With a preference for making art over cleaning and sealing grout, Graham could look forward to years of easy care with her new floor.

Homeowners Dallas and Marsha Graham installed tile pattern laminate throughout the first floor, including this bedroom.

Laminate flooring is made of several layers. At the core is the thickest layer, which is a high-density fiberboard. Under the core is a back layer that adds stability and acts as a moisture barrier, which is very important to prevent cupping.

Above the core is a pattern layer, which is essentially a photograph of almost any material you would use for a floor surface, usually hardwoods, stone or tile. Covering the pattern layer is a protective wear layer, many of which incorporate aluminum oxide for added durability.

You can use conventional woodworking tools on this flooring, although it’s a bit hard on the blades.

You can use standard wood cutting saws to cut laminate flooring, but the very things that make the newest flooring so tough are also hard on saw blades. Be prepared to sharpen or replace the blades when you are finished.

We used a portable table saw and our Dewalt 12-inch sliding compound miter saw (because it can reach all the way across the boards) to make most of our cuts. On both the table saw and the miter saw, the teeth enter the material from the top, which minimizes chipping. You can use your circular saw equipped with a carbide blade, but we recommend cutting from the back of the piece, especially if you have a net fit that will not be covered by base boards, such as against a shower stall or patio door.

Our Dewalt 12-inch sliding compound miter saw can reach all the way across to cut the pieces to length.

Make sure the subfloor is flat and free of nail heads, has no sizable holes and is clean. Because laminate floors float (are not fastened directly to the sub floor), they tend to bridge over low areas, which can leave a sinking feeling when walking on these areas. It’s best to get things flat within 3/16 inch or so over an area that can be tested with a 6-foot level.

Next, roll out an approved foam pad underlayment. This padding acts as a vapor barrier, smoothes out minor subfloor imperfections, insulates and dampens noise.

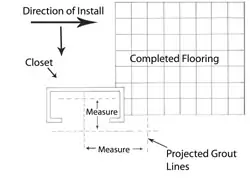

Each row steps back one tile so the head seams are offset while keeping the simulated grout lines in line with each other.

In the end, it doesn’t matter which direction tile pattern laminate floor boards are laid because the pattern components are square. So, do whatever makes the most sense to get the rectangular boards into place. Orienting the long side of the boards down a hallway, for example, could mean fewer cuts.

Also, read the instructions for your particular product when deciding which direction to work the floor. Many of the non-glue laminate floor systems require a specific order of installation such as left to right and top to bottom.

The flooring pieces tip in at an angle until the tongue and groove match up.

With wood-grain laminate floor patterns, you can use random lengths to begin and end each row of flooring as long as the seams don’t land too close to each other. This is not so with a tile pattern laminate floor. All of the grout lines must line up in both directions just like real tile.

Unlike real tile, however, each of these laminate pieces has multiple printed tiles in the pattern of each board. This adds a little more challenge to the layout, because you have to think in terms of making your cuts and overlaps based on where the printed grout lines fall.

Tap the joint together with a hammer and block.

You want to think “brick pattern” to off-set the joints of the boards while thinking “tile pattern” to keep the grout lines in line. This will all make a lot more sense when you open a box of flooring and get started.

Lessons from Ceramic

Another consideration with a tile pattern versus a wood-grain pattern is how the vertical lines in the layout fit the room. Before laying real ceramic tile it’s a good idea to position a row of tiles across the room to see how they will fit. Rarely will full tiles fit the room exactly so you must decide what size of cuts to have on the perimeters of the room.

You can usually find someone on the crew who’s willing to just stand there and add weight to the flooring so it doesn’t move too much when attaching the next piece.

In a room with an open wall on one side and lots of cabinets or furniture on the opposite wall, it may make sense to start with a full tile on the wall that will be seen. In other situations it may be best to split the difference so the tiles are cut about the same on both ends of the room. This can be particularly important when the layout involves a hallway where a thin cut of tile along one wall can look like a fat mistake.

You should also check the room for square, measuring to see if opposite walls are parallel. If you need to make a tapered cut along a particular wall, it’s better to do so with the largest tiles possible. In other words, don’t leave a thin row of cut tiles on a wall that is out of square. The farther you can get the initial grout line from the wall, the better.

Measure from a point that corresponds with an edge on the piece to be cut. Keep in mind that you will have door jambs, casing and base to cover the gaps to the walls, so don’t cut too tightly.

If you have a long floor transition between rooms, such as tile-to-carpet, it’s best to plan your layout so there are full tiles along that transition. You can either adjust the floor break location, or start the room with a row of cut boards along the wall opposite of the floor break so the layout works on full tiles.

All of these ceramic tile considerations apply with a tile pattern laminate floor as well, so take your time when deciding where to start that first full piece of material.

Lock and Load

Of course, once a row gets started it’s just a matter of adding full boards until another full one won’t fit. Measure the remaining distance to the wall and cut the final piece in the row from the end of the board that matches your snap-together tongue-and-groove pattern. The off-fall from this cut board will probably work (when trimmed to match a grout line on the previous row) on the other side of the room to start a new row.

You can run the table saw blade right up to the layout line.

Again, follow the product’s instructions for tipping and locking the pieces into place. Line up a piece to be installed so the head joint just clears, slip the tongue and groove together and put the piece flat on the floor. Use the tapping block to tighten the joint along the long edge of the board. Also, use the tapping block to lock the head joint seam together.

This is where the tile pattern is different from wood-grain patterns. In the process of locking in the head joint, you may shift the rows so the tile joints no longer align. It can help to have someone stand on the adjacent board or place a wedge at the end of the row against the wall.

Custom Cuts

When it’s time to make a cut, be sure that you are measuring from a point that corresponds with an edge on the piece to be cut. Turn the piece to be cut so the tongues and grooves are oriented like the pieces already installed.

We used a jigsaw to finish these notch-type cuts.

Don’t be shy about making pencil marks on the flooring. It’s easy to clean pencil lines off of the laminate surface so you can mark clearly where you want to begin and end cuts.

Don’t try to fit the floor too tightly inside the wall lines. Take advantage of the thickness of the baseboard material. You should have at least 1/4 inch of tolerance all the way around where the edges will be covered by door jambs (in new construction), casing or base.

There is no wait to move onto a no-glue laminate floor. When you’re done, it’s ready. Oh yeah, there is that install-the-baseboard thing, which will be followed by some spackle, caulk and paint touch-up. Then you’ll be ready to move onto your next project.

You may need to go to the end of a row and shift it back over to re-align the grout pattern.

Realignment

Locking the head seams together pushed this row of flooring boards under the drywall and misaligned the tile joints in the printed pattern. To fix this, cut out some drywall so you can slip the pull bar over the edge of the board to bring the row back in line. This shifting of the rows to keep the joint patterns in line is a constant challenge of working with tile pattern laminate flooring.

If you really want to get tricky, you can plan the new row to get knocked over a bit at each head joint. Figure about 1/8 inch per joint and start the first board offset a bit to the right. By the time you reach the right end you’ve gained a little with each board, but you’ll still need to make a slight adjustment to get the grout pattern to line up.

Closet Connection

Our project had three closets that had to be installed from the rear of the closet out to join the main room. To accomplish this we projected the grout line grid beyond the leading edge of the flooring in the main room and measured over to the closet area and back into the closet to determine where the grout lines would line up in both directions.

In most cases you will need to cut the back left piece to get the closet started on pattern with the rest of the floor. Additional boards can then be cut to align with the first board in the closet as you work your way out.

If a closet’s door opening faces the oncoming material (i.e. the natural flow of the install takes you into a closet), no special provisions will need to be made because of the orientation of the closet.

Materials:

• Laminate flooring

• Flooring underlayment pad

• Pull bar

• Tapping block

• Wood cutting saws

— table saw

— jigsaw

— circular saw

• Carpenter-equipped tool belt

— hammer

— tape

— pencils

— combo square

— utility knife

• Safety and comfort gear

— safety glasses

— ear plugs

— knee pads

Rock Floor Installation