When installing baseboards, crown molding (“moulding”) and chair rails, it’s tempting to cut 45-degree miters at the corners and hope for a sure fit. The problem is that most walls aren’t square. Joining two 45-cut molding pieces may give you a square joint, but a square joint may not work for your crazy corner. In fact, it seems like every wall is just a “hair” out of square. This problem could be due to a framing error or a buildup of drywall compound in the corner. But even a perfect miter joint can develop gaps when the wood dries and contracts in winter.

The first piece of molding should be butted squarely against the wall and fastened in place. The intersecting piece will be coped to fit the first.

Unlike miter joints, cope joints have one trim piece, such as the baseboard shown, butted against the adjacent wall at the corner. The joining trim piece is carefully cut to nest against the profile of the other. These joints eliminate the problem of out-of-square corners when installing trim, and they’re less likely to reveal a gap when the wood shrinks.

Cut an inside miter on the second piece of molding, cutting the piece a few inches longer than its final length. Then, use a pencil to outline the edge of the molding profile. Use a coping saw to cut along the pencil line, about 1/16″ to the waste side of the profile edge (lead photo).

Cutting Corners

To make a cope joint, butt the first piece of molding into the corner and fasten in place. The second piece of molding should be cut a few inches longer than its final length. On the intersecting end of the second piece, cut a 45-degree inside miter. Then run a carpenter’s pencil along the edge of the mitered profile, marking the shapes and curves for better visibility.

The traditional way to make the joint is with a coping saw. The thin, flexible blade of a coping saw is designed especially for cutting out intricate patterns. Clamp the second piece of molding securely to a work surface and use the coping saw to cut along the pencil line that marks the decorative pattern. It may help to angle the blade to back-cut the molding. Try to keep the blade about 1/16 inch to the waste side of the cutline.

Use a file to finish the joint, “fine-tuning” the small curves and edges.

When most of the wood is removed, use a file to finish up the cut and clean the profile, revealing a shaped edge that will be the only point of contact between the intersecting molding pieces. You want to remove all the wood from in front of the profile and create a socket that fits over the face of the first piece. I own a five-pack of files of various shapes, but for coping joints I mostly use a “rat tail” file, which has a round, slender shape that works well for “fine-tuning” small curves and edges. A flat file works well on square edges.

The finished coped joint should have a clean, shaped edge that nests easily against the face of the intersecting piece of molding.

Next, test-fit the molding against the first piece. Check for any gaps and sand or file away any high spots for a good fit. Once you’re satisfied, cut the molding to length, cutting the uncoped end square and butting it against the far corner to meet another coped piece on the next wall. Nail the molding in place and finish by caulking the seam. Proceed around the room to complete the installation.

How to Proceed

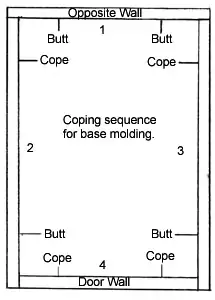

When coping molding, even the best carpenters have trouble creating the “perfect” joint. For the best looking installation, you should follow a certain order as shown in the diagram. For the sake of explanation, I’ll describe the procedure for a rectangular four-wall room with a single door. Begin on the wall that is opposite the door and install a piece that is square at both ends, flush between the two adjacent walls. This way, anyone walking into the room sees the best side of the joints. On the two adjacent or “side” walls, cope the joints where they meet the installed molding, butt cut the opposite ends square and but them against the “door wall.” The molding on this fourth wall should be coped on both ends, but the joints on the “door wall” are the least noticeable in the room in case of any minor imperfections.