How To Build Rustic-looking Doors on a Budget

By Rob Robillard

I was recently contacted through ConcordCarpenter.com with an email that started something like this: “Can you make me rustic looking cabinet doors quickly, cheaply, but built real well?”

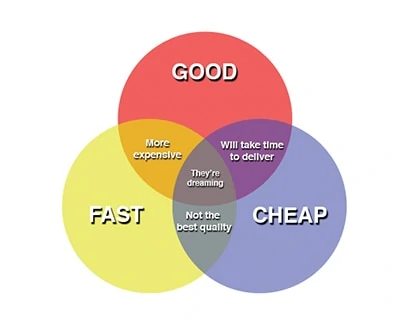

Fast, Good, Cheap Triangle

I’ve always tried to avoid doing anything cheaply and have half-jokingly followed the “Designers Holy Triangle.” The DHT is used when pricing a project; clients must choose only two out of the three options. They can’t have it all!

The Fast, Good, Cheap Triangle goes like this:

- Good + Fast = Expensive: Choose good and fast, and we will postpone everything else and make you our priority. We’ll work 24/7/365 to get your project done! But don’t expect it to be cheap.

- Good + Cheap = Slow: Choose good and cheap, and we will do a great job for a discounted price, but be patient because we want to do it during the winter while we’re having our lull.

- Fast + Cheap = Inferior: Choose fast and cheap and expect an inferior job delivered on time. You truly get what you pay for, and in my opinion this is the least favorable choice of the three.

Fishing, Shipping, a Love Story, and of course Beer!

While I would normally run away from a project request like this, I was drawn to this man’s story. He and his wife had recently purchased their dream house in Newburyport, Massachusetts. Located on the southern bank of the Merrimack River where it empties into the Atlantic Ocean, Newburyport has a long and rich history. Originally the area was inhabited by the Pawtucket Indians and later became a city in 1851. It was once a big fishing port, shipbuilding and shipping center, and was known for silverware manufacture. It’s also the location of NBPT Brewing Company—one of my favorite “beeaah” makers (said with a strong Boston accent).

According to my new client, his wife took ill and passed away. He really wanted to follow through and finish the dream project according to her original plan. Every time he spoke about her or the project his eyes would well with tears. How could I say no?

Designing the Doors

When we met, he brought a sample of the current French provincial style cabinet doors, which he wanted to replace. His plan was to keep the cabinet boxes and face-frames and apply new, rustic-looking doors. The doors would copy the old overlay design and be painted an olive green color.

I explained to him that I preferred to build my doors in a “Stile and Rail” or “Frame and Panel” method with a floating door panel. This method allows the door panel to fit into groves along the doorframe. Frame-and-panel construction, a method developed hundreds of years ago, deals well with the expansion and contraction that seasonal humidity has on solid wood cabinetry.

“Clearly there MUST be a cheaper, faster way?”

After some back and forth discussion, on door construction as well as the time/cost involved to make the doors traditionally, he asked me if I would glue strips to a door blank. This way the door would appear to have a solid panel with a faux rail and stile.

After some thought I told him could do that a lot faster, and with less machine setup, than construct the frame-and-panel doors. My only reservation with this idea is the doors will be susceptible to cupping and movement. He told me he didn’t care, and we agreed to start and keep the project to 16 hours of labor.

My client wanted to use pine and wanted me to incorporate the saw kerfs in the doors’ design. Rough sawn pine is used for many homeowner projects such as siding on sheds, fencing and birdhouses, so we thought it was the perfect choice for this project.

What is Rough Sawn?

Rough sawn lumber is left rough from the saw mill and usually needs to be dried, planed and otherwise dressed by the end user. Drying is often done by leaving the lumber outside, but it can also be dried in a lumber kiln or in your workshop. Often times you can purchase this lumber from the mill after it is kiln-dried.

Wood Species

There are a few species that are best suited for a rustic appearance. We chose kiln-dried, rough sawn Pine. It is a fairly popular choice for a rustic look because it displays the visible knots for which rustic kitchen cabinets are well known. Pine is also a sustainable resource, readily available and reasonably priced.

Selecting Material

We chose to get our rough sawn lumber from a local saw mill called Parlee Lumber & Box Co., Inc. Parlee was originally established as a gristmill and was converted to a sawmill in 1815.

Parlee had an assortment of 1/4-in. (4/4) and 2-in. thicknesses in addition to the following widths: 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 inches, and wider. We were able to purchase 4/4 x 18-in. wide boards.

Rough lumber thicknesses are measured in 1/4-in. increments. The thinnest rough-cut boards, labeled 4/4 and called “four quarter,” are 1-in. thick.

Tip: A common rule of thumb is to buy 10 to 20 percent more than you need (and I’m glad we did).

Don’t Forget the Countertop Overhang.

I made my client a sample door and drawer set to make sure he was getting what he wanted. I originally used a thickness planer to mill the 4/4 pine down to 3/4-in. thick and added the 1/4-in. strips, resulting in a finished thickness of 1 inch. The old doors were 3/4-in. thick, and the new doors left only a 1/2 in. of granite counter overhang. As a result we decided to split the difference and opted for a 7/8-in. thick finished product.

Measuring for Doors

Measuring was easy. My client brought me the entire set of doors and drawers, all I had to do was replicate the width and height of them. Having them in the shop as I worked was extremely helpful for reference.

Milling the Door Panels

Rough lumber is rarely flat or straight. I used the table saw to size the lumber and my 13-in. thickness planer to mill one side of the lumber down to just under 3/4 inch.

Carpenter Tip: Take the time to make a cut list and group all of your same size rips together.

This reduces the adjustments on your saw and is more time-efficient. Write your finished, cut sizes on the boards’ edges for future reference and to ensure you have made all the parts prior to moving onto the next task.

Milling 1/4 inch of wood off a board is a lot of work, puts wear and tear on your tools, and creates a ton of sawdust. I emptied my dust collector twice.

On the three largest doors I had to cut the lumber to fit into my thickness planer and then glue it back together again. I matched the rough sawn pattern and used dominos inside the joints to keep the panels aligned and give them strength.

Once I had the doors milled, I gave the rough sawn faces a light sanding to remove the splinters, dirt and other debris.

Milling the Rail-and-Stile Strips

Choosing a fairly standard stile and rail width, I ripped some of the rough pine boards down to 2-1/2-in. wide. I then flipped those boards on edge to rip them into 1/4-in. thick rough sawn strips. I set the table saw fence 1/4-in. off the blade to do this, keeping the rough sawn faces against the fence. By cutting both faces of this board I was able to get two pieces of rough sawn strips per board, and a 3/4-in. thick piece of cleanly cut pine for the scrap pile.

When ripping the strips I used a table saw and feather-board to keep the board tight to the fence.

I also used a sacrificial push block to move the board through and past the blade.

Note: On the drawers we reduced the faux strips to 2-1/4-in. wide for aesthetics.

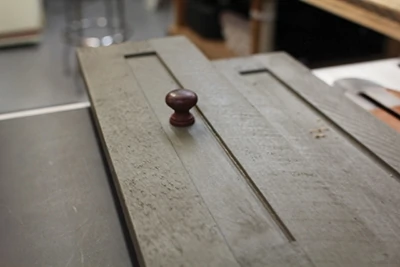

Applying the Frame-and-Panel Look

On traditional frame-and-panel doors the “stiles” always run from top to bottom along the sides and the “rails” fit between, and butt into the stiles.

After cutting one side of each strip square, I flushed the strip to the end of each rough sawn board and used a utility knife to mark the opposite end.

I made all the cuts on a miter saw, lightly eased the edges with a hand plane and then glued them to the rough sawn board with wood glue. A few well-placed pin nails held the strips in place until

I could apply clamps.

Once both of the “stiles” were applied I followed the same method for squaring, marking and cutting the “rail” strips.

“We’re Gonna Need More Clamps!”

This method of construction quickly eats up your supply of clamps, so make sure you have enough handy to do this before pouring the glue. Putting the glue back into the bottle is harder than getting it out!

To help with the shortage of clamps, I used strips of scrap pipe as “clamping cauls.” Cauls are used when clamping and gluing up project. Cauls provide better and more even pressure across the workpiece, beyond the reach of the clamp’s head. Cauls also allow you to reduce the number of clamps required on a glue-up.

Sand All Six Sides

I allowed a day for the strips to dry, filled any voids with wood filler and then sanded the faces with an orbital sander. When sanding, I focused on getting the style and rail strip intersections flush but used care not to eliminate the sawn marks.

I then took the door and drawer blanks to my Ridgid benchtop belt sander and carefully cleaned the edges, focusing on getting the applied strips flush with the rough sawn board.

Tip: The doors are longer than the sanding belt, so I “free-handed” the sanding procedure. This required me to carefully and evenly move the door back and forth along the sanding belt.

Drilling for Hinges and Knobs

We used a 35mm Forstner hinge cup drill bit in a drill press to make the door-hinge holes. I placed these holes in a slightly different location than on the older door hinges so as not to have to deal with the old screw holes in the cabinet case face-frames. These holes would be filled and painted by the painter and I wanted solid wood for my screws.

The client provided me with solid cherry knob pulls, and I simply centered and drilled these in the locations he desired.

For the hinges, we re-used the existing Blum Overlay Hinges designed for face-frames and replaced any as needed.

I like these hinges as they have a smooth, soft-closing action and are ideal for face-frame cabinets or any cabinet where clearance is an issue. Each hinge has three-way adjustability, are compact and are available in five different overlays, ranging from 3/8 to 1-3/8 inch.

Hanging the Doors

To save costs the client chose to paint and hang the doors. I mounted the hinges to the door so all he had to do was establish a reference point to keep all the doors the same height. I told him to make a small story pole or reference stick and use it at each door. Alternatively he could also install blue tape at the tops of every door and use a laser or level and make reference marks.

Whichever way he chooses, he is one step closer to accomplishing his dream house.

DIY Doors

This method is a fairly straightforward way to make a “frame-and-panel looking” door. If you have limited tools, you could do this with 3/4-in. stock and eliminate the thickness planer altogether.