Closet space is one of the most under utilized but totally upgradeable spaces in our homes—particularly linen and hall closets. In the houses I’ve worked in during my career, it seems that whether they’re new builds or old-time fixer-uppers, the closets are either painfully devoid of shelf space or packed with some wood and stick contraption a previous owner slapped together in the dark. So, while there are numerous and complex systems geared for creating a “clos-Mahal,” sometimes what you really need are basic shelves, or what comedian George Carlin called “a place for your stuff.” Here’s how to lay out and build basic closet shelves that optimize vertical space, look great and carry everything you need to store.

Planning

No matter what the project, you cannot underestimate the value of smart and thoughtful planning, and the first thing to consider is what you’ll store in the space. This will determine how you’ll space the shelves and how deep to make them. The closet we built in the “step-by-step” photos was an upfit for a bathroom in an 80-year-old house, so we spaced the shelves about 18 inches apart. This optimized the vertical space for bulkier items like stacks of folded towels while not wasting space for smaller but important items like toiletries and cleaning products. Spacing them equally also made the closet look neat and well-made.

Layout

Bottom Shelf. Since the shelves have thickness (we used 3/4-inch MDF), you can’t just run your tape measure up the wall in 16-inch increments because the shelves won’t end up evenly spaced. To get an even layout—18 inches from the top of one shelf to the bottom of the next—first determine and mark the bottom shelf. This provides the control point for the rest of the layout. Our bottom shelf was 36 inches off the floor to accommodate a hamper, so we measured 36 inches up, then leveled a line around the closet at that height.

Middle Shelves. From our first line, we measured up 18 3/4 inches. The extra 3/4 inch represents the thickness of the bottom shelf and the measurement shows us the bottom of the second shelf, which we again marked and leveled. We then repeated the process for the remaining shelves. For the top shelf, we left it about 24 inches below the ceiling so thicker, less often used items (like blankets for the adjacent guest room) could be stored there.

Shelf Depth. Every closet is different so shelf depths will vary from house to house. The key to a useful shelf is one you can fairly easily reach the back of. In this case we had a lot of space—but not too much—so we could make the shelves the full depth of the closet, 24 inches.

Stud Location

The key to this shelf installation is the 1-by-2 pine ledgers that carry the MDF shelf blanks. The ledgers must be fastened securely to studs for the shelves to be safe. If you’re lucky, your stud finder will locate the studs for you. Mine somehow never works, especially in thick plaster like we had here. If it doesn’t work, try the old-fashioned way: Rap your knuckles on the wall until you hear something solid and then punch holes in the wall just under the shelf line to see if that sound corresponds with a stud. Mark the width of the studs to guide your fastening. Don’t be surprised if you have to punch a bunch of holes before locating solid framing.

Ledger Layout

Rear-Wall Ledgers. Measure the width of the closet’s back wall first for the length of the first ledger. Since this piece will be covered by the side-wall ledgers, cut it about 1/8 inch short of the actual measurement. This accommodates for wall imperfections and still looks great. Cutting it exact or a hair too long invites tears in drywall tape or cracks in plaster when you try to tap it into place with your hammer. This measurement will also be your shelf width, which you’ll cut later. If the wall studs or plaster job are particularly gnarly, you may have to cut these individually.

Side-Wall Ledger Boards. On a 24-inch-deep shelf, the side-wall ledgers need to catch at least two wall studs, but don’t need to be as long as the shelf is deep, which means you can cantilever the shelf over the ends of the side-wall ledgers up to 6 inches, but running it about 3 inches over looks better. Measure the length of the side-wall ledgers. If you measure off the back wall, then remember to subtract 3/4 inch, because the side-wall ledgers cover the back-wall ledger when you nail them up.

Cutting

You can use a manual miter box to make your ledger cuts, but a power miter saw is the way to go here. Cut all your ledgers to length and store in separate stacks. You can also add some great detail to an otherwise bland ledger. Tool Tip: Set up a stop on your saw or work bench so instead of measuring each piece before you cut it, you can just press it up against the stop and cut. Less measuring, better accuracy.

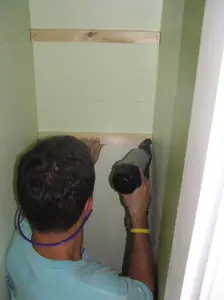

Installing Ledgers

Install the rear-wall ledgers first. Using a pneumatic nailer and 2-1/2-inch nails will make quick work of this process. Otherwise, use 2-1/2-inch trim drive screws (note: Make sure you pre-drill and countersink the ends to avoid splitting.) There is almost assuredly a stud in each corner of the closet behind the drywall; angling the fastener—called toe-nailing—usually helps make a solid connection. And, adding a few dabs of construction adhesive to the back of the ledger stock provides real belt-and-suspenders security.

Side-Wall Ledgers Next. Toe-nail or toe-screw the back of each side ledger to the corner closet stud. Make sure they’re flush with the rear-wall ledger. Nail to the remaining studs on the line. Tool Tip: This is where having an angled finish nailer really saves time and increases the quality of your work. The fasteners pierce all the layers of the wall—great for plaster—and sink solidly into the framing.

Cutting & Installing Shelves

Cut the shelves to the final dimensions. How you cut them depends on how big they are and what tools you have. In fact, we used several tools to size ours: A circular saw to rough-cut 4-by-8 sheets, a table saw to trim them and a miter saw to cut them to length. Tool Tip: A table saw is great for working with smaller sheet stock, but they were never designed for that work. So, if you don’t have a table saw, use a circ saw and a shoot board or straight edge to trim pieces to length. You might want to set up outside for cutting MDF, though; it creates a superfine dust when cut.

Top Shelf. The top shelf’s width needed to be trimmed because it laid out above the door head. If we made it full depth, it would cover the entire opening, so we made it 12 inches deep instead of the full 24 inches.

Lean In. The key to making the shelves fit through the door and onto the ledgers is to start with the bottom one. Tip it so it fits through the door opening, then lean one side down onto the ledger. Last, lean the other side down. Repeat for the remaining shelves. Some shelves may need to be trimmed or even re-cut depending upon imperfections in the closet wall, which you’ll see as you lay the shelves. Don’t be frustrated, you won’t be the first one it’s happened to.

Nail Down. Switch to 1-1/2-inch nails and nail the shelves to the ledgers. If you’re screwing, pre-drill and countersink the holes. Tool Tip: Nailing sheet goods is an ideal application for a pneumatic stapler. I use a narrow crown stapler for work like this.

Final Finish

We used MDF for these shelves because it can handle the load that would be put on it. For longer or wider shelves, it’s smart to either run a solid wood nosing on MDF to support the front, or use birch plywood, which will span a little further without sagging. We also used MDF because it accepts paint so well and we could make it match the closet interior perfectly.

To really integrate the shelves with the wall you can caulk or put shoe molding around their top surfaces to cover the gaps between their edges and the wall. Ours fit well enough that we could caulk the joint and then proceed to fill and sand all nail holes. After everything was dry, we primed and painted the shelves with latex paint. I like to wait a full seven days before loading a freshly painted surface to give the paint ample time to cure, otherwise, you run the risk of heavier items sticking to the paint and ruining your work. And ruined work really isn’t the point of home improvement in the first place, now is it?

Mark Clement is the author of The Carpenter’s Notebook