How to Make “Cope and Stick” Doors for Cabinets

By Rob Robillard

The terms “cope and stick,” “frame and panel,” and “stile and rail” are synonymous with a certain construction technique for doors. These terms are interchangeable and have long been a hallmark of fine cabinetry. I use “cope and stick” joinery because it makes a good looking and sturdy frame for cabinet doors.

“Cope and stick” construction is not new; it’s been around for hundreds of years and is useful to negate the effects of moisture on solid wood used to make doors, furniture and wainscoting.

I recently was asked to make a built-in cabinet for a remodel to match a client’s Shaker style doors, which featured flat panels and beveled stiles and rails.

Door Construction

In “cope and stick” door construction, the cabinet door frame is held together by a joint between the edge of the “stiles” (the vertical members of the frame) and the “rails” (the horizontal members of the frame).

The stiles are the longer parts of the door frame and receive the “sticking” (milled profile), and the rails are the shorter parts which receive the coped profile.

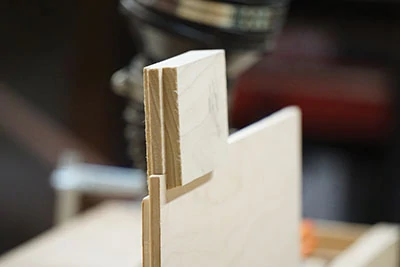

The “sticking”—the panel groove and the decorative profile on the interior edge of the frame—is matched by a special cut in the end of the rail called a “cope.”

To complete the joint, the two matching profiles are simply glued and clamped together. The strength of the joint relies on a near-perfect match between the cope and the sticking, which is achieved by using bits designed specifically for a shaper or router table.

The door panel is always sized slightly smaller than actual dimensions of the grooved style and rail frame. This allows the panel to expand and contract with seasonal humidity without affecting the stable shape and size of the door.

Construction consists of five members:

- Door panel

- Left vertical stile

- Right vertical stile

- Top horizontal rail

- Bottom horizontal rail

Larger doors may require a mid-rail or stile.

Sizing the Stiles and Rails

I used Poplar wood for my stiles and rails on the cabinet doors. I ripped all the parts on a table saw to 2-3/4 inches and ensured that I had one or two extra in case of a mis-cut or tear-out.

Once all the parts were ripped to width, I cleaned up the edges on a jointer before cutting them to length on a miter saw.

Note: Lay out the rails by adding 1 inch to the final inside width of the frame. That measurement will allow for a 1⁄2-in. sub-tenon on both ends of each rail.

Making multiple identical sized cuts, over and over again, is time consuming and can also lead to mistakes in measuring through graduated error. When cutting parts to the same length on a miter saw, it’s best to use a jig that allows you to measure once and make your repetitive cuts. I use a stop-block jig, either clamped to my miter saw fence or screwed to the miter table. When setting up this stop block, make sure you measure from the edge of the saw kerf to your block.

Reversible Shaper Bit Set

In order to make the “cope and stick” joint you either need a special router bit or use a shaper table with a shaper cutter.

There are a variety of matched bits available to use such as; ogee, bead edge, round edge and traditional. I’m a fan of the bead edge.

There is a wide variety of bits and shaper cutters available that cut “cope and stick” joints for cabinet dimensioned stock (3/4-in. standard thickness). These cutter sets are often called “stile and rail” sets.

A typical reversible set includes one cutter that cuts both the sticking and the cope, and one slot cutter for cutting a panel groove. Some manufacturers offer an additional kit with one more slot cutter which allows you to cut a rabbet below the sticking instead of a slot. This method is useful for making doors with glass or mirror panels.

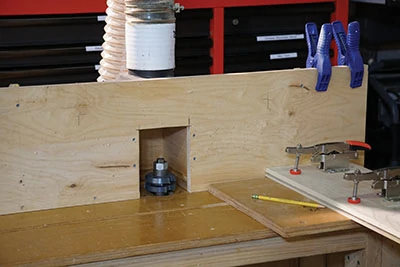

I use my shop-made shaper table and sleds with hold down clamps to cut all of my copes and sticks.

To make the raised panels, I use an old radial arm saw that I modified to become a permanent “panel-cutter.”

Construction steps:

- I start by making my cope cuts on the ends of my rails.

Tip: Use scrap wood and a “hold-down” sled to get the correct fit prior to cutting into your project wood.

- Reverse the shaper bit and rearrange it to cut the stiles profile.

Tip: I use the coped end to assist me in setting the bit’s height, aligning the slot-cutting wing with the tongue on the coped end.

- Cut a test board and check for fit. Although you can do this cut without a hold-down sled, I still use one.

- Holding your pieces, face-side down, cut the profiles on your stiles and rails.

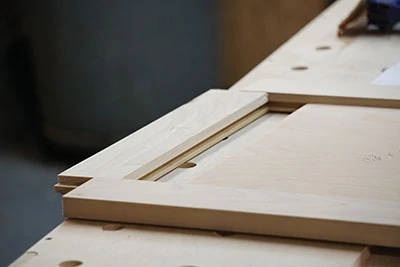

- Dry fit your pieces and measure for your panel.

- I make the panels on my panel cutter, taking several passes to get it to the right size to fit in the grooves. For flat panels, I simply put the bevel side in reverse.

Tip: Only apply glue to the joints between the rails and styles. No glue on the panel, it needs to “float” as it expands and contracts with seasonal movement. I allow 1/16 inch all around the panel for expansion.

Sourcing the Flat Panel

Typically, if I were doing this “old school,” I would glued-up panels of Poplar stock. Making a flat panel this way I have two choices:

Use a raised panel cutter to create a raised panel on one side with a continuous tenon. Then, orient the raised panel on the inside of the door (hidden from view) in order to get my flat panel look, or…

Run the stock through a thickness planer, bring the wood to 1/2- or 3/8-in. thickness, glue it up and achieve the flat panel. I would finish off this panel by using the shaper to create the tongue (continuous tenon) to insert into the groove of the stiles and rails.

On this project, we neither had the time nor the budget, so we used 1/2-in. birch plywood and used a Rockler rabbeting router bit to create the tongue (continuous tenon) to insert into the groove.

Tip: On the shaper, use a power feed or a clamp-down sled system like the ones in the photos. It’s safer and more accurate.

Dry Fit the Door Parts

Prior to making the raised panel, I dry fit the stiles and rails and ensure that I have the proper measurements. I also take into account a 3/16-in. reveal at the hinge side of both doors and between them.

Once the flat panel is made, I again dry fit everything prior to glue up.

Using a glue brush, I apply wood glue to the “cope and stick” portion of the stiles and rails. I do not put glue in the panel groove or on the panel tenon.

Glue and Clamping

Once the glue is applied, I place the unit onto two pipe clamps. The pipe clamps are applied at the joint connections only.

Prior to applying clamping pressure, I ensure the doors are square and also that the connections are flush.

To check square, I use diagonal measurements, a framing square and also 90-degree clamp blocks.

It’s also important to ensure that the door is not bowing: Look along the pipe clamp edge to see if you have a consistent reveal between the pipe and door stiles and rails. Sometimes I push the parts tight against the pipe.

Sand and Finish

Allow 24 hours for the glue to dry, remove the clamps and sand all the faces of the door. I like to flatten any raised edges at the “cope and stick” joint first. Then, I move on to sanding the flat surfaces to remove mill marks.

If left on the board face, mill marks often show up once the door is painted.

Editor’s Note: Robert Robillard is principal of a carpentry and renovation business located in Concord, Massachusetts, and editor of the blog, A Concord Carpenter, www.AConcordCarpenter.com.