By Matt Weber

A playground slide can bring tons of fun to the backyard.

A few years ago my young nephew discovered the wonders of a playground slide. It was love at first site. He was totally stoked over the rollercoaster rush of zooming downhill like a human skee ball. As he zipped down the chute, you could see the gleam in his eye. He was unstoppable … for about 1.5 seconds. The slide was only about 6 feet long. Still, he decided that having one of his very own would suit him just fine.

He presented a very persuasive argument in favor of my building him one, explaining that vigorous outdoor activity, such as sliding, would bolster his physical development at his critical stage of childhood. He reasoned that laziness, video game addiction and “couch potato syndrome” was the sad vice of far too many children these days, and it was my responsibility as his uncle to nurture his burgeoning athleticism and overall health by providing such sliding opportunities whenever possible. Cultivating such a positive environment in which to grow up, he explained, would pay off in spades when he matured into a well-rounded, world-renowned champion of some sort, destined to earn millions, which he would then graciously share with me as a gesture of gratitude for the thoughtful encouragement I had paid him in early years.

I was sold, but reminded him that if he jumped track and began to follow the path of juvenile delinquency, that the “slide box” could be retrofitted with a roof and iron bars to serve as a backyard detainment hut for wayward youths. He considered my caveat for a moment, and then agreed to remain a fine, upstanding citizen.

So I agreed to build the slide.

From the Ground Up

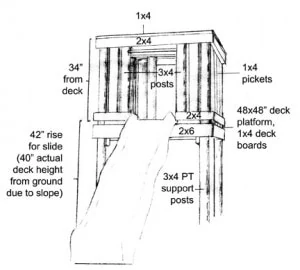

The playground slide shown was built using a standard joist design, supported by 3-by-4 posts and secured with galvanized fasteners. All fasteners exposed to the outdoors must be weather-resistant, galvanized, zinc-coated or stainless steel.

Standard homeowner tools are all you’ll need to complete it—a tape measure, post-hole digger, circular saw, sawhorses and a level. A good drill/driver is a great tool if using decking screws as fasteners. And while there’s nothing wrong with the old hammer-and-nail approach, you can’t beat a high-quality framing nailer if you tackle a lot of construction projects.

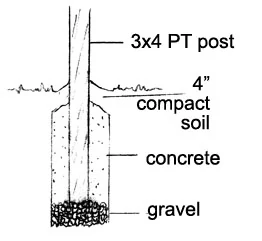

Before starting, check your local codes to make sure you’re allowed to build on the proposed location and that you properly anchor your posts according to regulations, type of soil and geographic location. Footings are required to support the posts, and as a rule these have to extend 6 inches below the frost line—this will be 2 feet deep in many locations. The diameter of the posthole should be three times the post diameter.

To set a post, compact the bottom of the hole and place 6 inches of gravel or crushed stone in the hole for drainage. Place the 8-foot pressure-treated post and make sure it is level and plumb. Tack temporary strips of lumber to the post to help brace it. Pour dry, fast-setting concrete mix into the hole until it reaches about 4 inches from the top. Recheck that the post is plumb and level. You’ll need to keep the temporary bracing in place while the concrete cures. Pour water onto the concrete mix and allow it to soak in. About 1 gallon of water is required for each 50-pound bag of dry mix. When dry, fill the remainder of the hole with dirt, sloping it away from the post and tamping it down.

Brace the support posts while the concrete cures.

Repeat this process for each of the four posts, making sure the outside corners of each post is square with the adjacent posts. The concrete sets up in about 40 minutes, but wait about 4 hours before putting any weight on the posts. I laid out the posts with about 45 inches between each outside corner, so when the joists were added, I’d have a square 48-inch platform.

Framing the “Box”

Our purchased plastic slide was designed for a 42-inch-high deck. However, I was building on a downhill slope. To account for the slope, I made a mark 42 inches up the front post and held the slide in position at the mark. I found that due to the slope, with a 42-inch deck height, the slide would be a couple of inches shy of reaching the ground. So I dropped the mark a couple of inches so the slide would have a solid footing. This new mark (40 inches on the front post) is where I need the surface of the deck to be to allow the slide a 42-inch overall rise.

Knowing the finished height, I planned the deck construction in reverse. With the posts still braced in place, I fastened four 2-by-6 floor joists in a square around the outside of the posts. The top of the front joists ended up being 39-1/4 inches high on the “slide” side of the platform, so when the 1-by-4 decking is added, it equals the required deck height of 40 inches. Fasten the joints with lag bolts or three galvanized fasteners into each end. Butt the joists together for a flush 90-degree corner.

A center joist supports the decking. At the corner support posts, I added some extra blocking to provide a solid nailing surface below the deck boards at the platform’s edge.

Inside the square joist frame I then fastened a third center joist to run perpendicular to the direction of the decking boards. You can toenail the center joist or use metal joist hangers to secure the ends. Once the joist system is in place, you can remove the temporary bracing.

Next, I fastened the 1-by-4 pressure-treated decking boards across the joists, perpendicular to the center joist, spacing them evenly 1/2 inch apart to allow for easy drainage. Secure each deck board on top of the 2-by-6 supports with two galvanized fasteners in each joist. The deck boards should be cut to fit flush over the joists (mine were each about 48 inches long). At the edges of the platform you’ll have to cut the decking to fit between the corner posts. Because the edge boards fit flush between the posts, I nailed blocking beneath them at the post intersection to provide a secure nailing surface below.

Rails and Pickets

I decided the deck’s rail system should be about 34 inches high. I installed 2-by-4’s in a square around the support posts. The top edges of the 2-by-4s were 34 inches above the deck. Make sure the corners are square and flush, and everything is level. Then, use a handsaw or circular saw to cut the posts off flush with the top of the 2-by-4 framing.

A circular saw and a portable workstation will come in handy throughout construction.

The front and rear of the platform need an opening, one to climb into and one to slide out. I framed these two openings with 3-by-4 posts, spaced 19 inches apart, which were fastened on top of the decking from beneath the platform. The tops of these posts were cut flush with the upper edge of the top framing and fastened securely to the inside of the 2-by-4s.

Install the pickets or balusters closely, so no small hands or feet can get stuck between them.

I also installed a square frame of 2-by-4 face boards surrounding the corner posts where they meet the surface of the deck. Both the upper and lower 2-by-4 frames provide a secure nailing surface for the pickets (also called balusters) of the platform walls. You’ll have to leave an opening in the lower frame boards where the 2-by-4s meet the “door” posts to allow for the 19-inch-wide entrance and egress.

A high-quality framing nailer, like this model from Hitachi, can dramatically speed up assembly.

The four walls of the platform—except for the two openings—are completed by fastening 1-by-4 pickets evenly along the interior of the 2-by-4 framing. It’s important to keep the pickets tightly spaced, less than 1 inch, to prevent various kid-sized appendages from getting stuck between them. For a finished look, I crowned the posts, pickets and 2-by-4’s with a 1-by-6 cap board with mitered corners, which I fastened flat down onto the tops of the framing.

Step to It

You can build a simple set of steps using a pair of 2-by-4’s as stair stringers. I mitered the corners of the 2-by-4’s and fastened them to the face of the joist beneath the rear entrance to the platform, mounting them with 45-degree metal hangers. I spaced these stringers 14-1/2 inches apart. To determine the number of treads for stairs, measure the rise (vertical height) from the ground to the top of the deck and divide that distance by 7 inches (standard tread height). The resulting number indicates the number of treads or steps you’ll need. However, since these stairs are built for short legs, you might opt to use a shorter tread height. When you’ve determined your measurements, mark the tread locations on the stringers before installing.

A high-quality framing nailer, like this model from Hitachi, can dramatically speed up assembly.

I used 1-by-6 stock for the treads. You can fasten these to the inside of the stringers using metal hangers. Or, you can support the treads as shown in the photo by using 2-by-6 blocking that is mitered to fit flush beneath each tread, on each side of the step. If using the blocking, begin construction with the very bottom blocking and tread, and work upward. Fasten the blocking to the inside of the stringers. Then fasten the tread from the top edges down into the blocking beneath.

To help minimize water damage to the wood steps, I placed a concrete landscaping paver beneath the foot of the stringers.

Fasten the slide to the deck with the included hardware.

Time for the Slide

The purchased plastic slide we used came with the necessary hardware to install it. Just drill mounting holes and twist on a few large bolts and washers, and the slide is ready for action.

Note: Despite the temptation to lubricate the slide with silicone spray in order to maximize child velocity, Extreme How-To strongly advises against this.

Add handles above the steps so they are easier to climb.

Lastly, I installed a couple of plastic handles on the entrance posts, about 8 inches above the deck, to give the kids an easy place to grab and climb up.

Add a grab bar above the slide so the kids can position themselves at the top of the slide for maximum velocity.

And above the slide exit, just a couple of inches below the 2-by-4 framing, I used a spade bit to mount a metal tube as a grab bar, so the little folks can safely situate themselves in launch mode.

The slide was complete, and Owen loved it. Not only did he employ it as his very own flight-training simulator, but he staked claim to the slide box as the official new location of his personal headquarters, where he plots all his secret plans and important missions.